Considered the first day of the summer season in traditional European societies, the first day of May has been celebrated in many ways over many centuries. May Day is related to the Celtic festival of Beltane and the Germanic festival of Walpurgis Night. May Day falls half a year from November 1 (Samhain, Hallowe’en, and All Saints’ Day) and it has traditionally been an occasion for popular and often raucous celebrations.

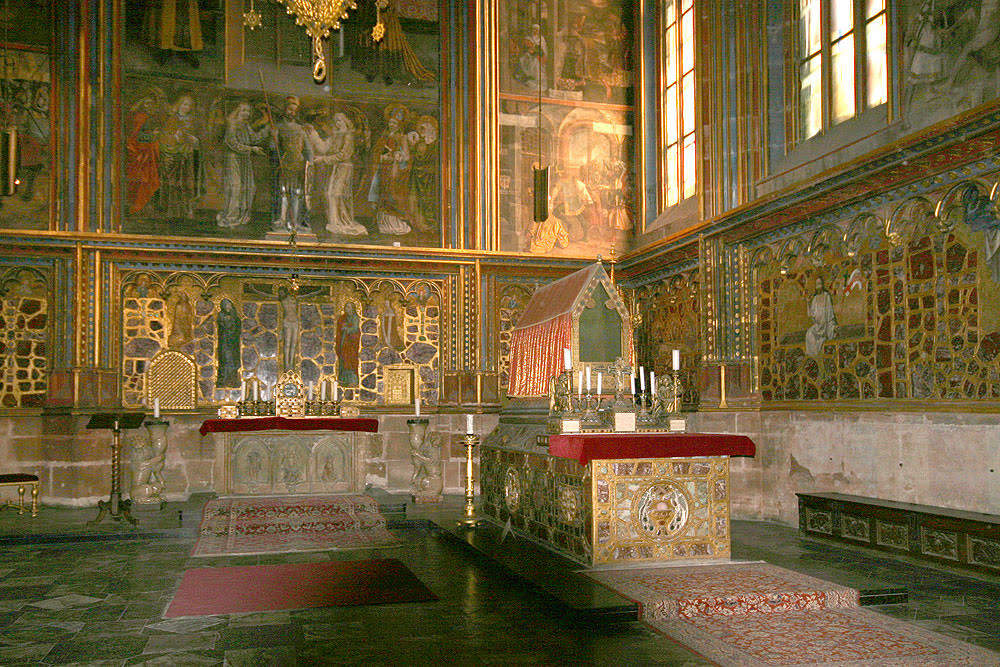

The earliest May Day celebrations appeared in pre-Christian times, with the festival of Flora, the Roman goddess of flowers, and the Walpurgis Night celebrations of the Germanic countries. It is also associated with the Gaelic Beltane. Many pagan celebrations were abandoned or Christianized during the process of conversion in Europe. A more secular version of May Day continues to be observed in Europe and America. In this form, May Day may be best known for its tradition of dancing the maypole dance and crowning of the Queen of the May. Fading in popularity since the late 20th century is the giving of “May baskets”, small baskets of sweets and/or flowers, usually left anonymously on neighbors’ doorsteps. (I remember making May Baskets in school and field day Maypoles on the playground.)

The day was a traditional summer holiday in many pre-Christian European pagan cultures. While February 1 was the first day of Spring, May 1 was the first day of summer; hence, the summer solstice on June 25 (now June 21) was Midsummer.

In Oxford, it is traditional for May Morning revellers to gather below the Great Tower of Magdalen College at 6:00 a.m. to listen to the college choir sing traditional madrigals as a conclusion to the previous night’s celebrations.

On May Day, the Romanians celebrate the arminden (or armindeni), the beginning of summer, symbolically tied with the protection of crops and farm animals. The name comes from Slavonic Jeremiinŭ dĭnĭ, meaning the prophet Jeremiah’s feast day, but the celebration rites and habits of this day are apotropaic and pagan, possibly originating in the cult of the god Pan.

The day is also called ziua pelinului (mugwort day) or ziua bețivilor (drunkards’ day) and it is celebrated to insure good wine in autumn and, for people and farm animals alike, good health and protection from the elements of nature (storms, hail, illness, pests). People would have parties outdoors with fiddlers and it was customary to eat roast lamb, as well as new mutton cheese and drink mugwort-flavoured wine to refresh the blood and get protection from diseases. On the way back from the parties, the men wear lilac or mugwort flowers on their hats.

Other May Day practices in many places include people washing their faces with the morning dew (for good health) and adorning the gates for good luck and abundance with green branches or with birch saplings (for the houses with maiden girls). The entries to the animals’ shelters are also adorned with green branches. All branches are left in place until the wheat harvest when they are used in the fire which will bake the first bread from the new wheat.