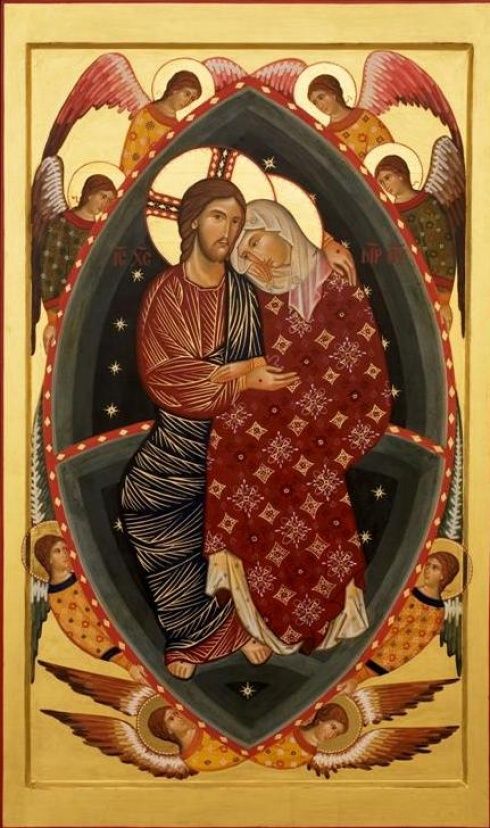

“Is he your Son, O Virgin of virgins? Is he your beloved, O most beautiful of women? ‘Clearly so… he is my Son, O daughters of Jerusalem (Song of Songs 5:9, 16). My beloved is love itself… and is found in whosoever is born of him.'”

In one of his sermons for the Nativity of the Mother of God, St. Guerric of Igny places these words from the Song of Songs on the lips of the Virgin Mary when he–the preacher–asks the Virgin to tell the congregation listening to the sermon about her Beloved, who is her Son. In this sermon, the “daughters of Jerusalem” are the monks and visitors listening to the sermon. These daughters of Jerusalem are also claimed as children of the Virgin as well: St. Guerric preaches that “she desires to form her Only-begotten in all those who are her children by adoption…. she nurtures them every day until they reach the stature of the perfect man, the maturity of her Son [Ephesians 4:13], whom she brought forth once and for all.” All those in whom love is found are members of her Son and thus her children by adoption and she nurtures them to share more completely in that Love which took flesh in her womb.

Just as St. Paul labored to give birth to Christ in his spiritual children (Galatians 4:19), the Mother of God is the mother of all those in whom Christ is born. “She herself, like the Church of which she is the type, is the mother of all who are reborn to life,” St. Guerric preached. What Mary gives the world, clothed with flesh, the Church gives us clothed with words, bread, wine, water, and oil. As the daughters of Jerusalem, we–no less than those who heard St. Guerric first preach his sermons–are privileged to nurture Love within us and among us as children of Mary, members of her Only-begotten.

St. Guerric of Igny (died 1157) was a scholar who became a disciple of St. Bernard of Clairvaux and took monastic vows to remain in St. Bernard’s community. But in 1138 St. Guerric was sent by St. Bernard to be the second abbot at the new monastery of Igny, near Rheims. As abbot there, St. Guerric became famous for the sermons he preached. His sermons for Advent-Christmas-Epiphany-Purification are especially stunning. Find translations of his sermons here.