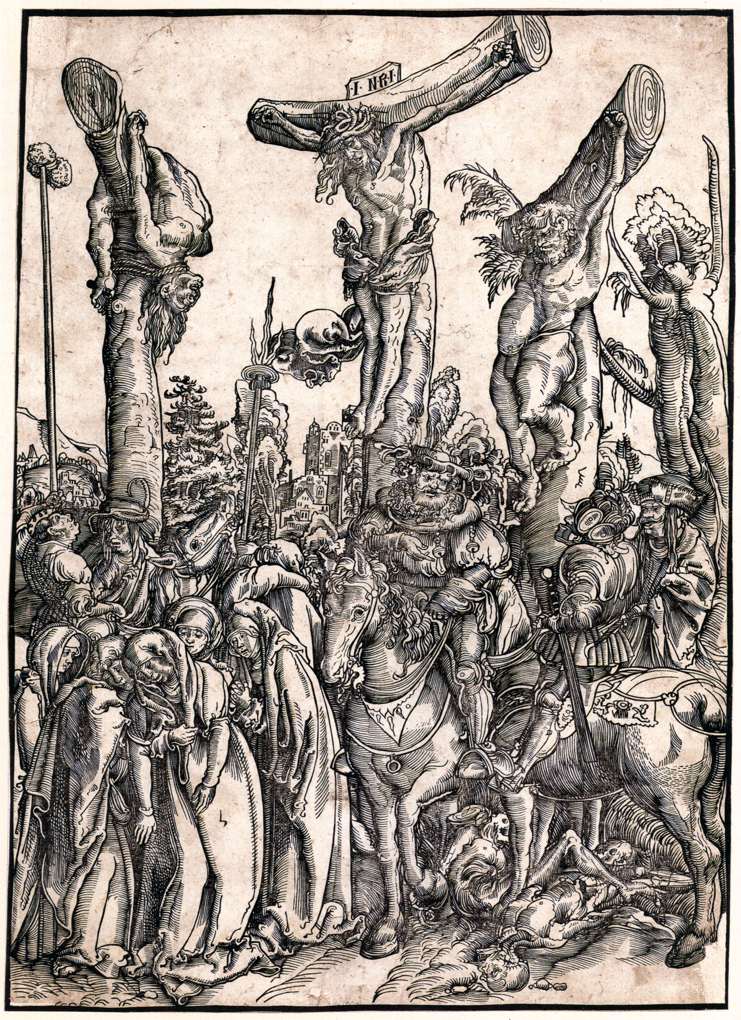

A detail showing Christ and the two theives on their crosses from “The Crucifixion” by Cranach the Elder (woodcut from approx. 1500-1504)

Holy Week, the days between Palm Sunday and Easter, is one of the most important and busiest times of the year in traditional European societies. Everyone is busy baking and cleaning and preparing for the great festival. There are many church services, especially at the end of the week on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday.

One of the more fascinating or frightening folktales of Holy Week tells us that in Prague and the Czech countryside, underground vaults, caves, and holes that contain hidden treasure will open up shine with a faint light as the Passion is chanted in church. A treasure-seeker can go outside church then and see these places and mark them to come back later. Or, if the treasure-seeker can’t wait to get rich, he can go inside the caves right then but he must get out before the last verse of the Passion reading is complete as the vault or cave will shut when the reading is complete and the treasure-seeker will be trapped inside until the next year.

In Russia, the tale is told that anyone who dies on Good Friday will be ushered directly into heaven just as the Good Thief was. (Many artists who painted depictions of the two thieves actually used the bodies of criminals who had been executed on the wheel as their models as no one was crucified any more; if you look closely, you can still see the thieves’ limbs twisted and bent in strange ways that don’t match descriptions of crucifixions because of their torture on the wheel.)

Much of the folklore associated with Holy Week involves protection of various sorts: To protect against the evil eye, wax from candles burned in church during the Holy Week services would be stuck to the heads of children or animals. Hanging a wreath on the door after sunset on Good Friday will protect the house against lightning. Hot cross buns baked on Good Friday and hung in the kitchen will protect against poverty and if they are hug over the bed, will protect against nightmares.