A view of the St. Agnes convent in Prague; the national museum’s stunning collection of medieval art is displayed here.

In the well-known Christmas carol, “Good King Wenceslaus looked out” from his castle in Prague and saw a poor beggar struggling to get home during a blizzard. The king asked his page if he knew who the poor man was and the page answered that he did; the poor man, the page told the king, that the poor man lived several miles away in a hovel near beneath the bluffs overlooking the river that runs through Prague. The poor man’s house was also on the edge of the forest, near “St. Agnes’ fountain.”

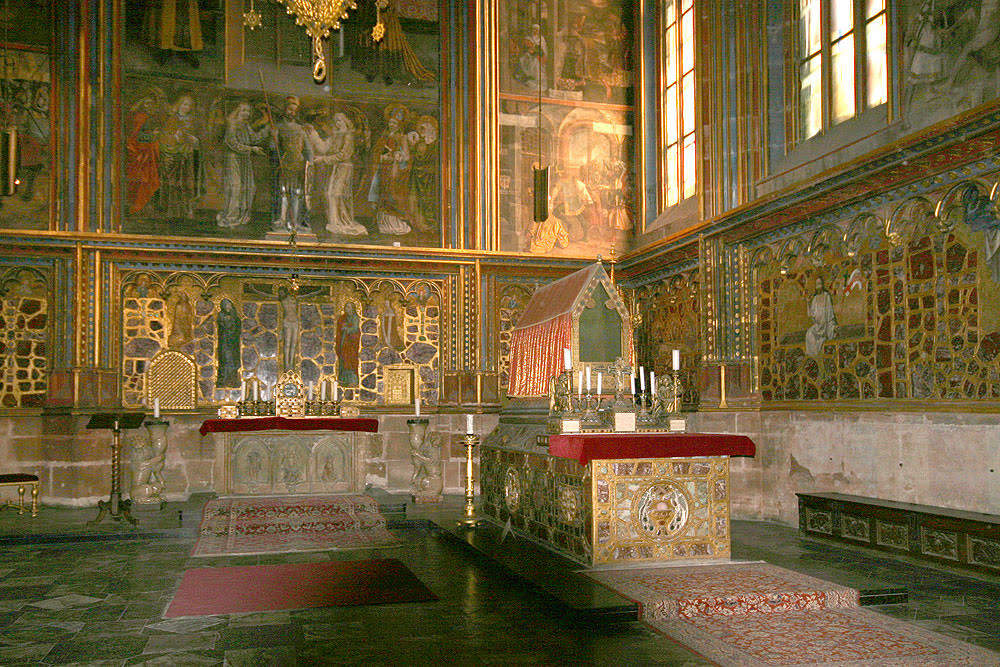

St. Agnes was a Czech princess who was born in AD 1200. She became a Franciscan nun–known as “Poor Clares”–and established a convent along the edge of the river, on what was then the edge of the city, right against the forest and in the shadow of the bluff on the other saide of the river. There was a well and a fountain in the convent courtyard which the nuns used for their drinking water. The convent is now the site where the National Museum of the Czeck Republic displays the collection of medieval art.

The princess shared a name with a much earlier St. Agnes, a young woman who lived inn Rome and who was executed for her Christian faith during the Great Persecution of Diocletian in AD 304; this Agnes refused to marry because she wanted to embrace life as a Christian ascetic. Agnes’ bones are conserved beneath the high altar in the church of Sant’Agnese fuori le mura in Rome, built over the catacomb that housed her tomb. Her skull is preserved in a separate chapel in the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone in Rome’s Piazza Navona.

According to Robert Ellsberg, in his book Blessed Among all Women: Women Saints, Prophets, and Witnesses for our Time,

“…the story of Agnes the opposition is not between sex and virginity. The conflict is between a young woman’s power in Christ to define her own identity versus a patriarchal culture’s claim to identify her in terms of her sexuality. According to the view shared by her ‘suitors’ and the state, if she would not be one man’s wife, she might as well be every man’s whore. Failing these options, she might as well be dead. Agnes did not choose death. She chose not to worship the gods of her culture. …Espoused to Christ, she was beyond the power of any man to ‘have his way with her’. ‘Virgin’ in this case is another way of saying Free Woman.”

This Roman St. Agnes was very popular throughout Europe during the Middle Ages. The well and fountain in Prague might have been associated with a church dedicated to her even before the princess built her famous convent there.

The young woman martyred in Rome was a member of a very prominent and wealthy family, which is why the Roman authorities cared that she had embraced the illegal Christian faith. The princess who became a nun evidently knew St. Clare herself, the founder of the Franciscan nuns and a friend of St. Francis of Assisi. Both women named Agnes–the Roman virgin-martyr and the Czech virgin-princess-nun–live on in the Christmas carol we sing every December.