Marking the 40th day after Christmas, Candlemas celebrates the triumph of light/spring over darkness/winter. Candles blessed on this day were among the most powerful talismans available to ordinary folk in the Middle Ages.

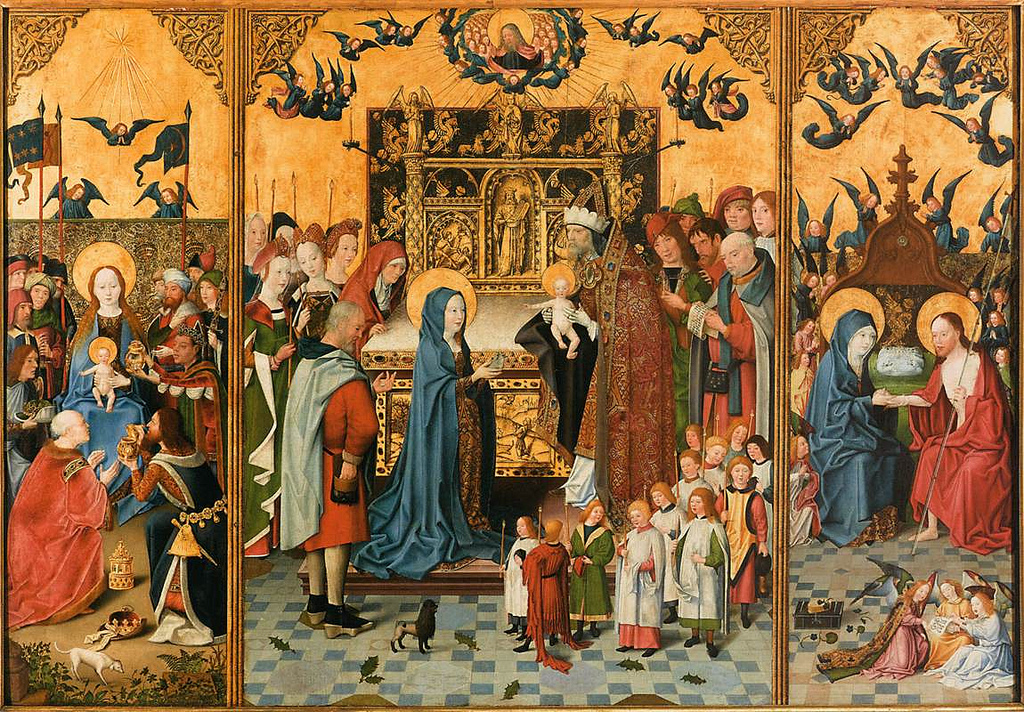

Candlemas, the name taken from the custom of blessing the year’s supply of candles on this day, is the 40th day after Christmas and marks the day Jesus was brought into the Temple by the Mother of God and acclaimed by the elder Simeon as “the light of revelation to the Gentiles and the glory of … Israel.” He also told the Mother of God that a sword would pierce her own heart during the ministry of her Son.

Candlemas, attached to the older feast of Imbolc and the quarter-day between Winter Solstice and Vernal Equinox and thus marking the first day of spring, was even more popular than Christmas in many areas (such as those under the influence of Byzantium and Byzantine Christian culture). People would flock to the churches to obtain the candles blessed on this day as the power of these candles to dispel darkness, death, illness, demons, and nearly anything else that might be considered dangerous to humans was widely reputed to make them the most powerful weapons in the medieval arsenal against evil.

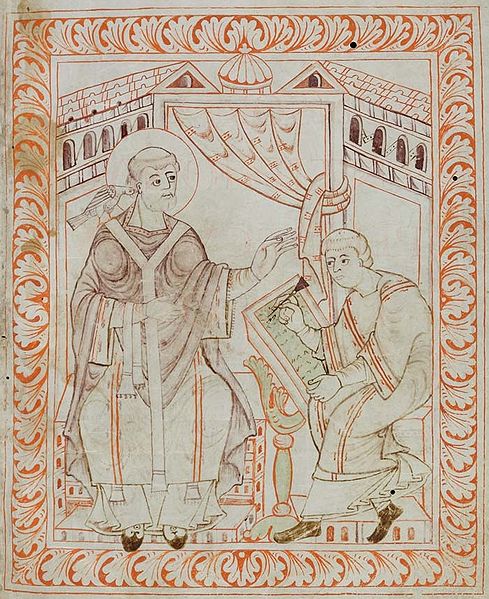

It was also common in western Europe for new archbishops or other leading churchmen to receive their pallium (the “stole,” a vestment similar to a scarf that drapes around the shoulders) on this day, woven from wool sheared from lambs on St. Agnes’ day (January 21).