In this interior view of the Church of St. Roch in Lisbon, you can see the famously expensive Chapel of St. John the Baptist. One reason it was so expensive os the large amount of lapis lazuli used on the front of the altar and the walls of the chapel.

My recent post about St. Roch was much more popular–and sparked some very interesting comments and responses–than I had anticipated and prompted me to think a little bit more about the good saint.

The most famous church dedicated to St. Roch is in Lisbon, Portugal. (There are a half dozen churches dedicated to him in the metropolitan area of New York City.) The church in Lisbon was the earliest Jesuit church in the Portuguese world, and one of the first Jesuit churches anywhere. The Igreja de São Roque was one of the few buildings in Lisbon to survive the disastrous 1755 earthquake relatively unscathed.

When built in the 16th century it was the first Jesuit church designed in the “auditorium-church” style specifically for preaching. It contains a number of chapels; the most notable is the 18th-century Chapel of St. John the Baptist which was constructed in Rome of many precious stones and disassembled, shipped, and reconstructed at São Roque in Lisbon; at the time it was reportedly the most expensive chapel in Europe.

The history of the church is fascinating. In 1505 Lisbon was being ravaged by the plague, which had arrived by ship from Italy. The king and the court were even forced to flee Lisbon for a while. The site of São Roque, outside the city walls (now an area known as the Bairro Alto), became a cemetery for plague victims. At the same time the King of Portugal sent to Venice for a relic of St. Roch, the patron saint of plague victims, whose body had been brought to Venice in 1485. The relic was sent by the Venetian government, and it was carried in procession up the hill to the plague cemetery.

The inhabitants of Lisbon then decided to erect a shrine on the site to house the relic. This early shrine had a “Plague Courtyard” for the burial of plague victims next to the shrine. In 1540, after the founding of the Society of Jesus in the 1530s, the king of Portugal invited them to come to Lisbon and the first Jesuits soon arrived. They settled first in All Saints Hospital (which no longer exists). However they soon began looking for a larger, more permanent location for their main church, and selected the Shrine of St. Roch as their favored site. They used the old shrine for a while but built the current church in 1555-1565.

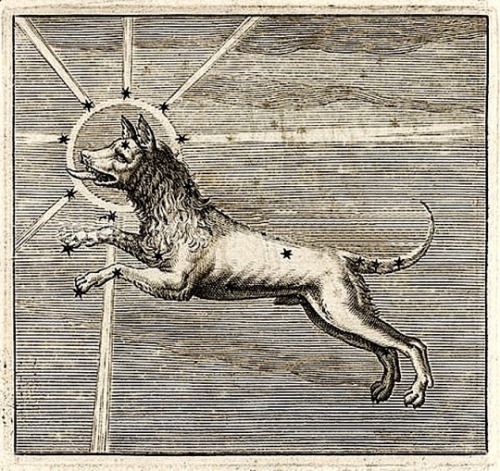

St. Roch himself is usually represented in the garb of a pilgrim, often lifting his tunic to demonstrate the plague sore, or bubo, in his thigh, and accompanied by a dog carrying a loaf in its mouth. The Third Order of Saint Francis claims him as a member and includes his feast on its own calendar of saints, observing it on August 17. There is a popular street festival in his honor in Little Italy at the end of August each summer; read about it here.