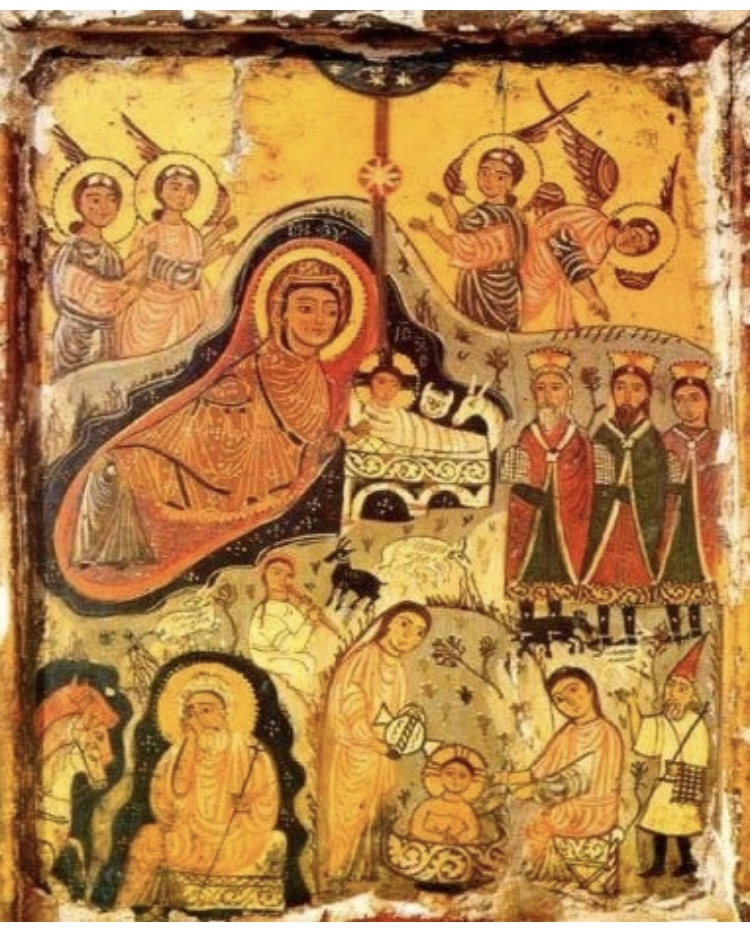

A Coptic icon of the Annunciation, showing the angel Gabriel presenting a lily as he announces the Incarnation to the Mother of God.

The elevation of the Host in a contemporary celebration of the Solemn Mass by Dominican religious.

Working together with God, then, we also entreat you not to receive the grace of God in vain. For he says: “In a favorable time I listened to you; on the day of salvation I helped you” (Isaiah 49:8). Behold, now it is the favorable time; behold, now is the day of salvation. (2 Cor. 6:1-2)

Synergountes de kai parakaloumen …. Synergy. Working together. Cooperation. We only experience “salvation” by working together with God. Any day we work together with him is the day of salvation.

Working together = cooperation with = synergy (fancy theological jargon)

Synergy = salvation

The classic, most clear example of synergy is the cooperation of the Mother of God with the request to bear the Word-made-flesh: “Be it unto me according to your word,” she answered the angel Gabriel. She cooperated with the request of God and the world was saved. If she had said “No,” we can only hope that God had a Plan B but there is no guarantee of that.

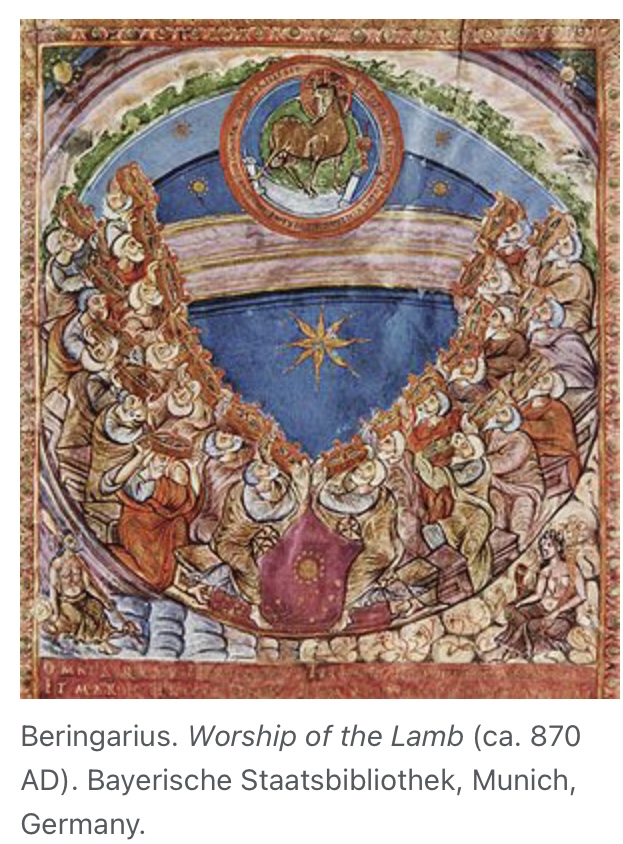

The Mother of God cooperated with God and the world was saved. We each personally make that salvation OURS when we approach the Holy Communion to receive the Body and Blood of Christ, harmonizing and uniting our Self with him. During the theological debates of what is the minimum necessary for an authentic celebration of the Eucharist, some said the Words of Institution (“This is my Body… Blood”) were the minimum necessary. Others said the invocation of the Holy Spirit (“Send down Your most holy Spirit to make this bread the Body of your Son ….”) was the minimum necessary.

What both sides presumed but never stated was that the priest also lent his hand to Christ to make the sign of the Cross over the Holy Gifts of bread and wine. The physical gesture was just as important–just as necessary–as the words theologians argued about. The priest’s hand had to cooperate/synergize with the words that he was saying and with the gestures that the Church expected him to make.

The priest’s gesture is as necessary as the priest’s words. That’s true for all of us. What we DO is just as important as what we say. “If someone says, ‘I love God,’ but hates a fellow believer, that person is a liar; for if we don’t love people we can see, how can we love God, whom we cannot see?” (1 John 4:20)