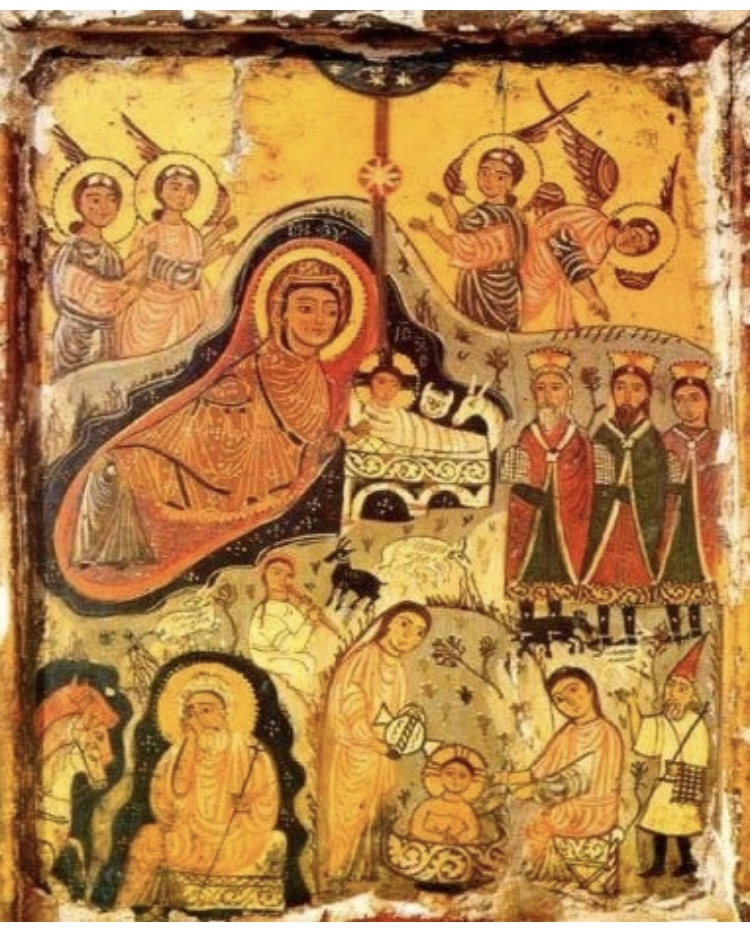

“Doubting midwife?” Where did she come from? There is no mention of a midwife in Matthew’s or Luke’s account of Christ’s nativity. This woman is the “Doubting Thomas” of the Nativity cycle.

According to the Protoevangelium, Joseph brings the Blessed Virgin to Bethlehem but as there is “no room at the inn,” he settles her in a stable–a cave, not a barn–as her labor begins. He goes to find midwives to assist in the birth.

Joseph quickly finds a pair of local midwives and brings them back to the stable-cave but none of them can enter because of the brilliant light shining within. As the light gradually fades, they are able to see the Virgin and the newborn baby. They enter and begin to tend to mother and child.

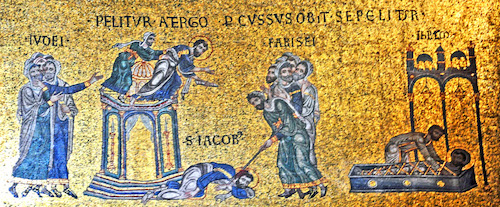

The first midwife washes and examines the new mother and is startled to discover that Blessed Mary is still a virgin. She reports this to the other midwife who doubts this and reaches out to examine Blessed Mary herself. But her hand withers as it nears the Virgin’s birth canal and even feels as if it were burning. She quickly withdraws her hand but it remains paralyzed and withered; as she struggles to assist in washing the newborn baby, she is healed by touching the child or by the water splashing from the tub–different versions of the story report both styles of healing. This second, doubting midwife proclaims that the new mother is indeed still a virgin and that the miraculous withering-healing of her hand is the sign of this and the miraculous nature of the new baby.

The midwife–who is eventually identified as Salome, possibly the same Salome that brings myrrh to Christ’s tomb with Mary Magdalen–has the same experience as Moses at the burning bush. Moses’ hand withers and is struck with leprosy because he asks for proof that it is truly God who is speaking to him. Isaiah is purged by a burning coal from the heavenly altar, just as the midwife’s hand feels as if it is burning. The midwife exclaims, “Woe is me! Because of my lawlessness and unbelief!” just as Isaiah exclaimed, “Woe is me! I am a man of unclean lips and I dwell among a people of unclean lips!” The midwife’s healing is also an allusion to the healing of the woman with the 12-years issue of blood who is healed simply by touching the hem of Christ’s garment in the crowd.

Just as the Apostle Thomas says he will not believe that Christ is risen unless he touches the wounds in Christ’s hands and side, the midwife cannot believe the report of the first midwife unless she also touches the evidence of the miracle. The disbelief of the apostle and the midwife is healed by touch; both Thomas and Salome testify to the truth of God’s action in the world because they have handled the evidence themselves.

Why is it important that the Mother of God remain ever-virgin? Her perpetual virginity is a safeguard of our status as brothers and sisters of Christ; if she had other biological children who were biological relatives of Christ, it would relegate Christian believers to second-rank status in the Church. Some members–the biological relatives–would be MORE the “brothers and sisters of Christ” than other believers who were not biological relatives. In order to avoid this two-tier system in the Church and to prevent a dynasty of Christ’s relatives from ruling the nascent Christian community, it was important that Mary have no other biological children. (We see in the Gospels themselves that she had no other children or Christ would not need to commend her to the care of St. John, the Beloved Disciple, at the Crucifixion. Those people the Gospels refer to as Christ’s brothers and sisters were his cousins or stepbrothers and stepsisters, the children of Joseph’s first marriage.)

Read my prior post about the stable-cave in which Christ was born here.

Read my prior post about the goldfinch often seen in portrayals of the Virgin and Child here.