Then I looked, and … another angel came out of the Temple and called in a loud voice… “Put in your sickle and harvest for the hour of the harvest has come, for the harvest of the earth is fully ripe. (Apocalypse 14:14-15)

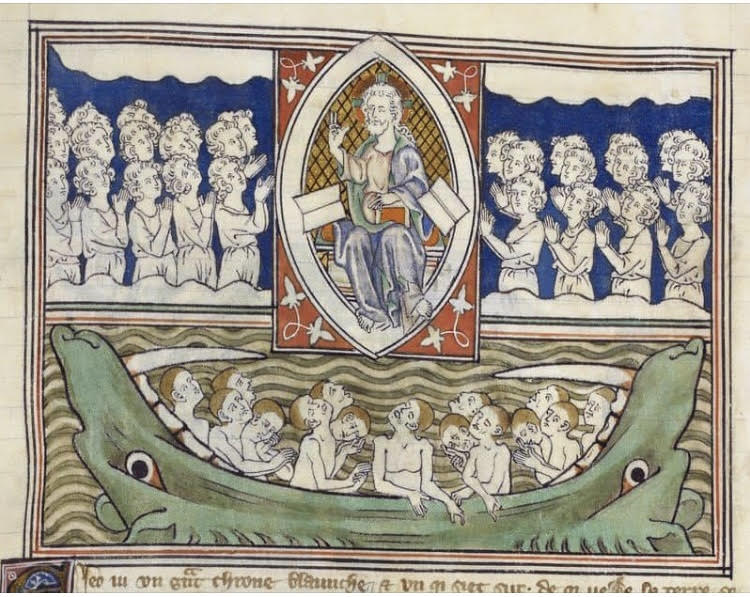

In much of the New Testament (Matthew 13) or the Old Testament prophets (Isaiah 17, Jeremiah 51, Joel 3), the images or parables about the harvest use the image of “harvest” as a way to talk about the Last Judgment, the End of Days. Often, the idea of harvest includes the idea of condemnation: the wicked will be harvested and condemned to their eternal punishment. But in the Apocalypse, the idea of harvest is about salvation rather than condemnation. The righteous are ripe–they have withstood the test of persecution–and they are harvested in the Apocalypse, not the wicked; the righteous are harvested and gathered before the Throne of God as crops are gathered into a barn for safekeeping.

But after the righteous are harvested, the wicked are gathered into the divine winepress. The “great winepress of God’s wrath” (Apoc. 14:19) is outside the heavenly city, just as the Cross was erected outside the walls of Jerusalem. The winepress grinds up those flung into it and their blood pours out as the grape juice flows from a winepress on earth, ready to be made into wine. Christ is flung into the divine winepress on the Cross and his blood pours out into the chalice of the Eucharist; in the Apocalypse, the wicked are thrown into the divine winepress which is outside the city–outside the Church–and they are trodden as grapes are trodden. But they do not emerge from the winepress victorious, as the martyrs do. The wicked are destroyed in the winepress because they choose to align themselves with the dragon–all the powers that oppose God and the Lamb.

Harvest and winepress. Bread and wine. How we choose to prepare for (1 Cor. 11) or respond to these experiences results in our salvation or condemnation. Often in ways that we do not expect.