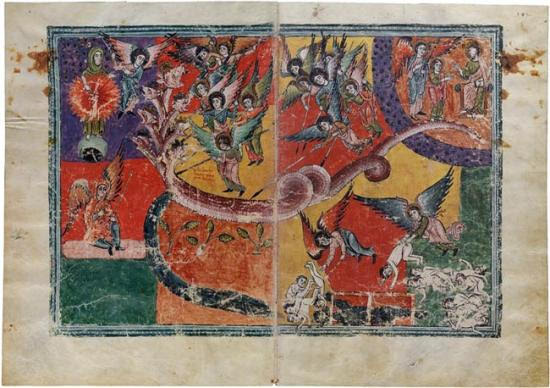

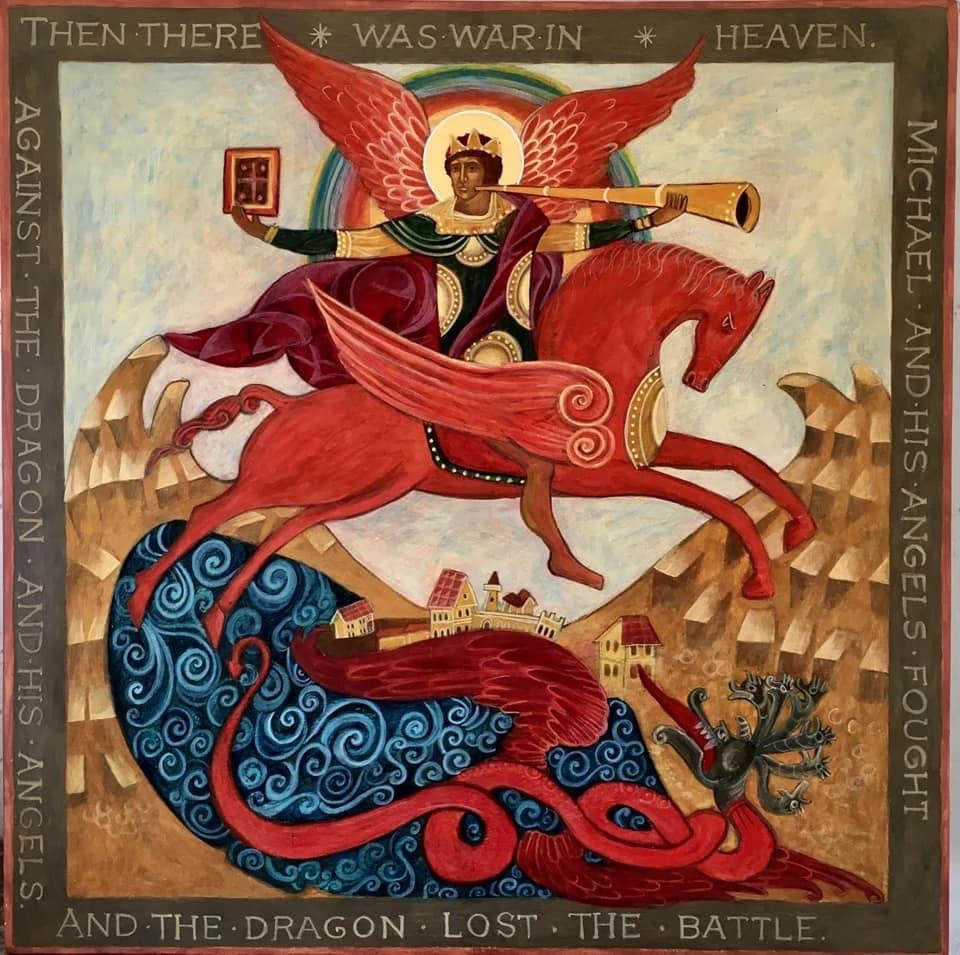

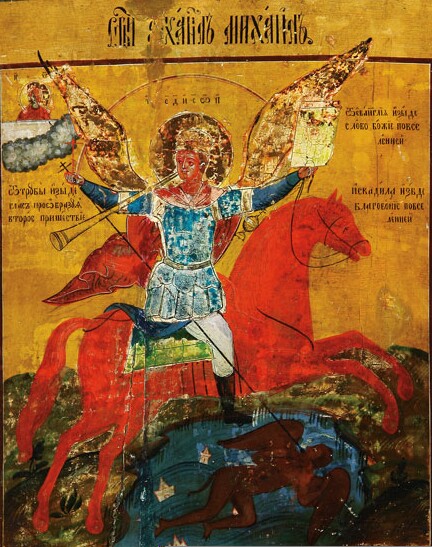

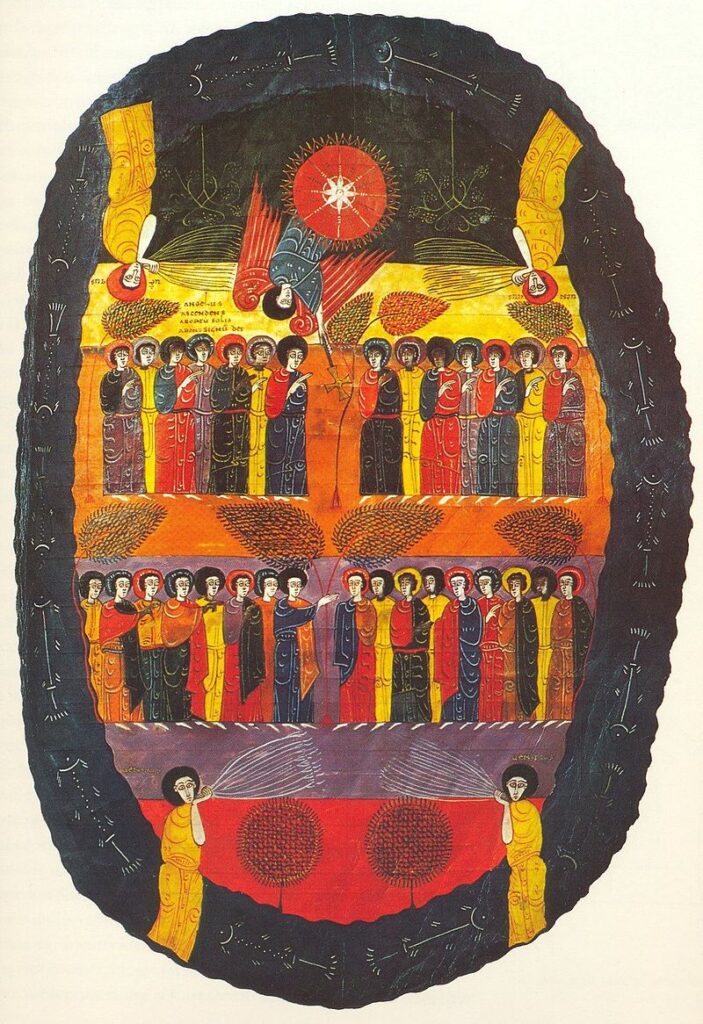

Then I looked, and there before me was the Lamb, standing on Mount Zion, and with him 144,000 who had his name and his Father’s name written on their foreheads. And I heard a sound from heaven like the roar of rushing waters and like a loud peal of thunder. The sound I heard was like that of harpists playing their harps. And they sang a new song before the throne and before the four living creatures and the elders. No one could learn the song except the 144,000 who had been redeemed from the earth. (Apocalypse 14:1-3)

SO much to say about such a brief passage! Modern commentaries often claim that the 144,000 are the Messianic Jews who accept that Jesus is the Messiah but in the early Church there was no such distinction between ethnic Jews and Gentile Christians. Classic commentaries by church Fathers interpret the 144,000 as emblematic of the perfected Church–12x12x1000 being the 12 apostles x 12 tribes of Israel x 1000 (perfection). That is also why the 1,000 year reign of Christ is an emblem of history perfected, not a literal 1,000 years as we know the cycle of 365 days x 1000.

The new song of the new day of salvation grows out of the song of deliverance sung by Israel on the shore of the Red Sea after the Exodus. (Have I told y’all about this already? I think I have.) The new song is also the Sanctus (“Holy! Holy! Holy!”) sung by the angels as they stand around the Throne of God and which we join them singing during the celebration of the Eucharist. During the Eucharist, we stand with the 144,000 before the Throne–together with the elders (presbyters) and four living creatures; together, we sing the Sanctus and give thanks for all that the Holy Trinity have done for us.

The saved are marked with the name of the Lamb and his Father, just as the followers of the Beast are marked by the diabolic number. But the classic commentary on the Apocalypse by Tyconius has something very different to say: according to Tyconius, the diabolic mark of the Beast is not described in Chapter 13. Rather, the number at the end of Chapter 13 is “616” and is “the number of a [certain] man,” i.e. the Son of Man, the Lamb of God. The number 616 is the total of alpha and omega, the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet and refer to Christ. It is also the total of the letters XIS, the first and last letters of “Christ Jesus.” Therefore, Tyconius understands the numbers 616 to indicate the famous Chi Rho emblem of Christianity. It is this emblem which is described as marked on the 144,000 at the beginning of Chapter 14.

Other early commentators say that the sign marked on the 144,000 is the cross drawn in chrism-oil by the bishop with his thumb when converts were baptized.

How’s that for a totally unexpected set of ideas about the 666 that we discussed last week?!