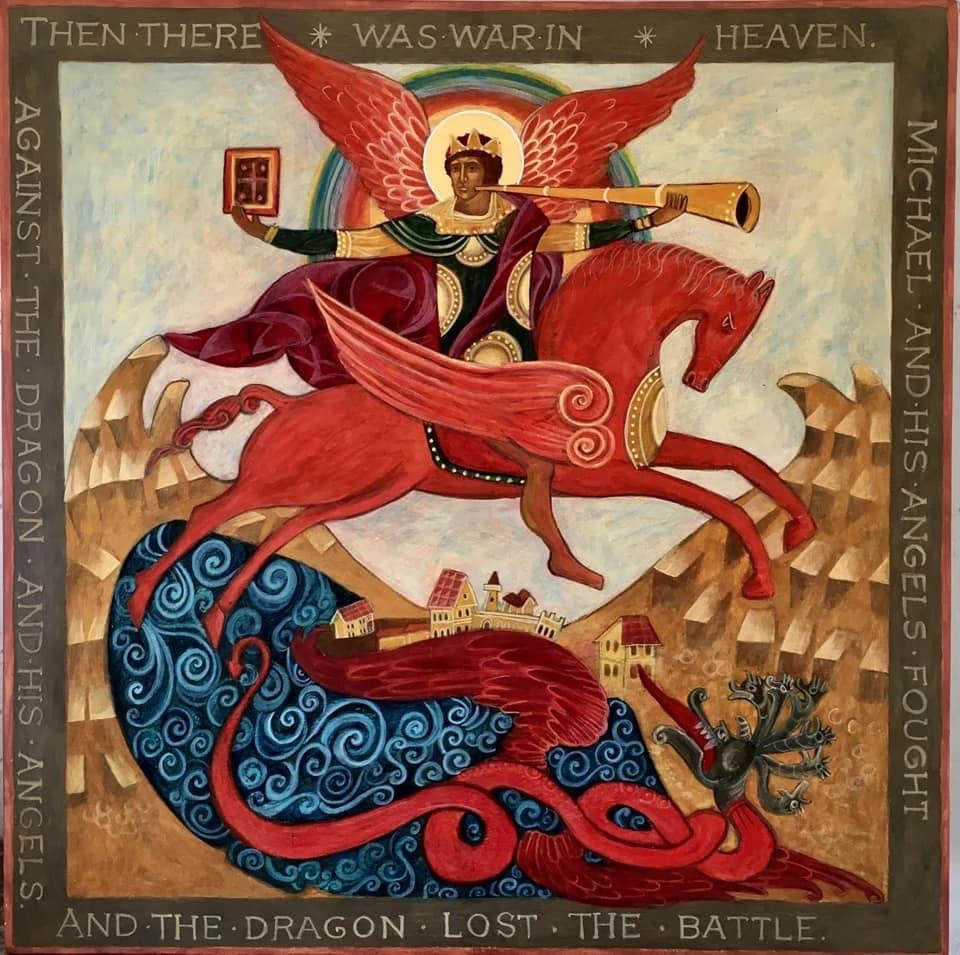

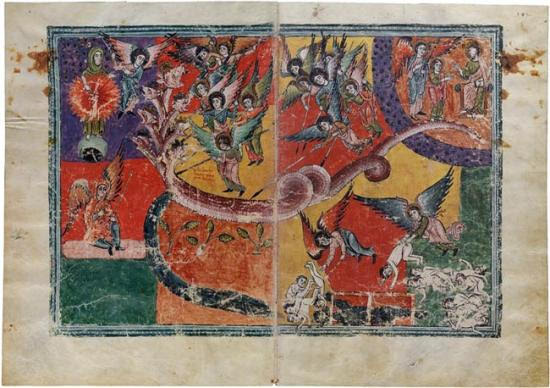

Then war broke out in heaven. Michael and his angels fought against the dragon. The dragon and his angels fought back and he did not prevail…. The great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent who is called Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world…. (Apocalypse 12:7-9)

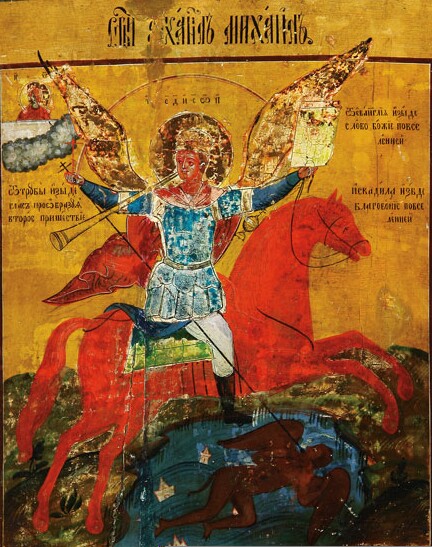

The Archangel Michael (Jude 9) is the captain of God’s armies and the champion of the Chosen People (Daniel 10:21, 12:1); in the Old Testament, he is the most powerful figure, second only to God. Although Satan does occasionally appear in heaven (Job 1), he is definitively cast down and overthrown here.

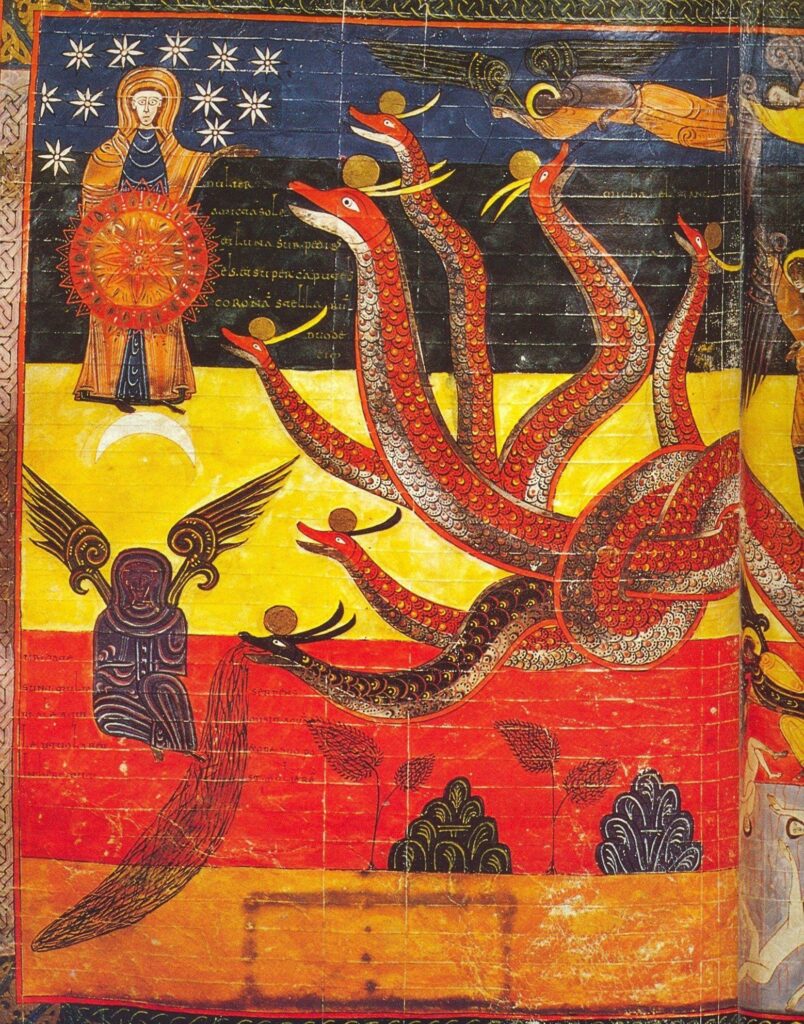

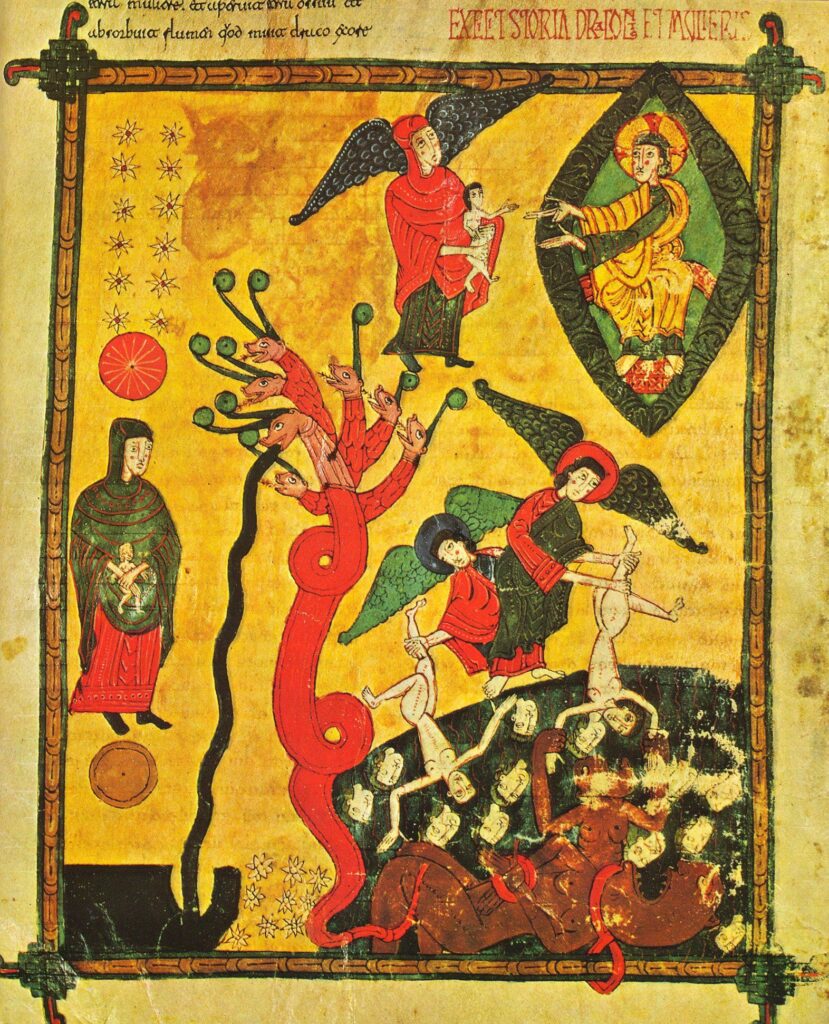

The dragon is identified both with the serpent who tempted Eve and with the adversary, the accuser who demanded that God allow him to test the sincerity of both Job and the Apostle Peter (Luke 22:31). Satan wanted to ruin them both but did not succeed. Satan, the dragon, wants to ruin the human race. He wants to ruin the entire creation. His jealousy goads him to want to destroy everything (Wisdom 1-2) but in the end, his jealousy destroys only himself.

Often the spear that St. Michael uses to fight the dragon with is a wooden lance; it is by the wood of the Cross that the dragon is overthrown. The archangel Michael’s victory is the heavenly and symbolic counterpart of Jesus hanging-dying on the Cross. The martyrs, as members of the Body of Christ, who testify-witness about the victory of the Cross, share in this victory but the victory is demonstrated by their dying as Christ died on the Cross. The events described in chapter 12 of the Apocalypse—the woman clothed with the sun, the dragon, the war in heaven—are the central events of the Apocalypse, around which everything else revolves, because they are the representation of the central events of earthly history.

“I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven,” says Jesus (Luke 10:18); therefore the apostles are able to cast out devils who possess humans. The Lamb, “who was slain from the foundation of the world,” is both eternally the victor and the one who wins the victory at a particular time-place in the world. Both the eternal victory and the victory in time are true; neither victory cancels or outweighs the other.

The dragon is not simply THE Devil, a single angelic personality. The dragon is all the enemies of God at once; in Ezekiel 29:3 and 32:2-3, we read that the Pharaoh of the Exodus is “like a dragon in the sea,” a great water monster who attempts to devour the Chosen People. The dragon is the Roman system which attempts to eradicate the Church. The dragon is everything and everyone who attempts to deny the victory of the Cross.