For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ: though he was rich, he became poor for your sake, so that you might become rich by his poverty …. For if that desire is present, the gift will be acceptable according to what one may have, not according to what one does not. (2 Cor. 8:9, 12)

St. Paul is raising money to aid the parish in Jerusalem because there is a famine there, adding to the political troubles facing the area which would soon boil over into open revolt against Rome and cause the Romans to tear down the Temple. He’s saying that the Corinthians will get “credit” from God based on what they want to give, even if their actual financial situation does not allow them to be as generous as they would like to be.

It’s always tricky to talk about God giving “credit” to humans. But we understand that impulse because we honor the intention if the person is unable to follow through, through no fault of their own. It’s a different situation if the person promises what they know they cannot deliver, raising hopes that can never be achieved.

God acknowledges–gives “credit”–our faith, our hopes and trust in him, and in our brothers and sisters. So this passage of 2 Corinthians is about more than fundraising. St. Paul is also talking about how we become rich through Christ’s poverty even if we don’t always follow through on being poor in spirit, forgiving as we have been forgiven, sharing our resources with those who have less–less time, less cash, less emotional bandwidth to bear whatever their current situation is. If we WANT to be as forgiving and as poor in spirit, etc. that’s at least a start. It’s something. Even if we don’t always live up to our intentions. But as the famous Easter sermon says,

… the Master is gracious and receives the last, even as the first; he gives rest to him that comes at the eleventh hour, just as to him who has labored from the first. He has mercy upon the last and cares for the first; to the one he gives, and to the other he is gracious. He both honors the work and praises the intention.

Paschal Homily, attributed to St. John Chrysostom

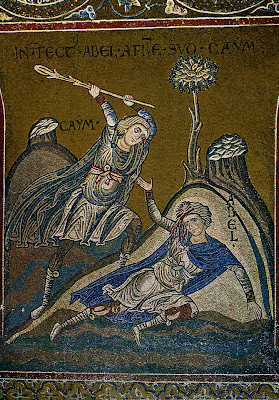

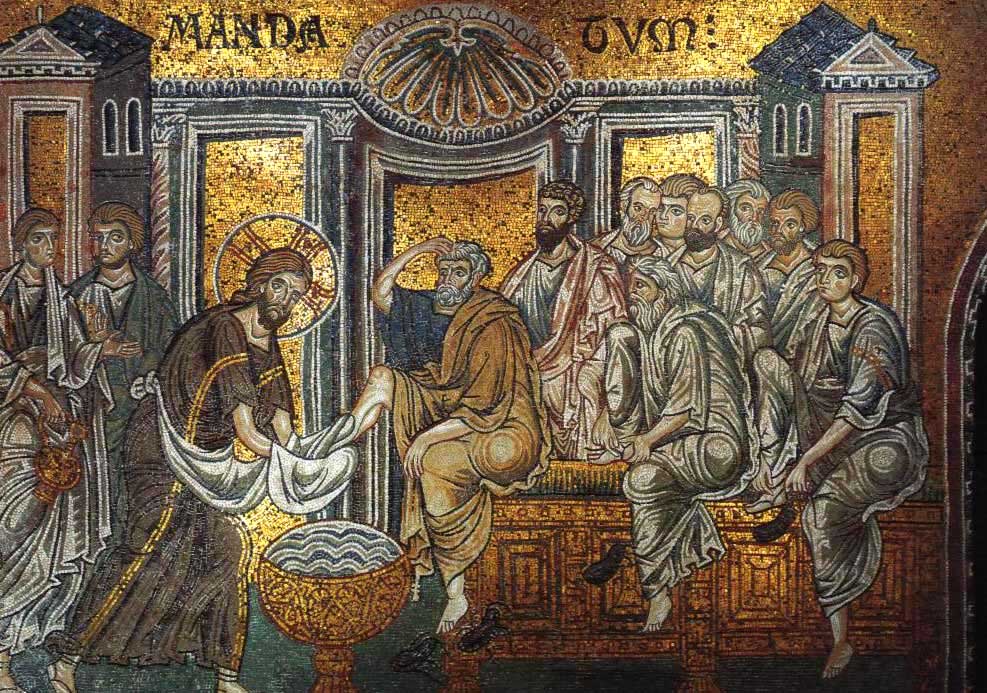

Christ takes off all his clothes in order to wear a towel and wash our feet. He hangs naked on the Cross. Holy Week makes us rich. The point of wealth is to share it. How can we share some of what we are given during Holy Week? Even if we can’t do everything we want to make those riches accessible to ourselves or others, we can at least do something. We can do a little bit more than we did last year. We can be present. We can at least begin to want to intend to receive those riches and then share them with someone else.

What human being could know all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge hidden in Christ and concealed under the poverty of his humanity? … When he assumed our mortality and overcame death, he manifested himself in poverty but he promised riches–though they might be deferred; he did not lose them as if they were taken away from him. How great is the multitude of his sweetness which he hides from those who fear him but which he reveals to those who hope in him!

St. Augustine of Hippo, On the Nativity 194.3