If anyone does not love the Lord, let him be anathema. Maranatha! The grace of the Lord Jesus be with you. My love for all of you in Christ Jesus. (1 Cor. 16:22-24)

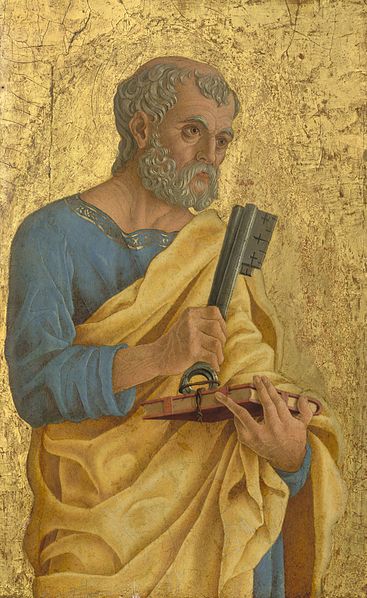

These sentences are part of the postscript, the “P.S.” that St. Paul adds in his own handwriting at the end of this first letter to the parish in Corinth. “Anathema” is “cursed” and is the same word the ecumenical councils use when denouncing the teachings that were condemned: “If anyone teaches that the Word is not divine in the same way the Father is divine, let that person be anathema!” Anathema marks those who are excluded from the fellowship of the Church, the Body of Christ.

Although St. Paul had difficult and challenging things to say to the Corinthians, he repeatedly stresses his love for them and that he does not want any one of them to be lost or cast aside. His love for the Corinthians–as a parish community and for each of them personally–is always his prime motivation.

“Maranatha!” can be translated several ways, which is why many translations today leave it untranslated. It can mean, “Come, our Lord!” Or it can mean, “Our Lord comes!” Both meanings are appropriate and maybe St. Paul meant the Corinthians to hear both meanings at the same time. Liturgical practice–described in the Didache— from about the same time that St. Paul was writing these words used “Maranatha!” as the people’s response to the invitation to receive Holy Communion at the Eucharist.

By this one word–Maranatha!–Paul strikes fear into them all. But not only that: he points out the way of virtue. As our love for God’s coming intensifies, there is no kind of sin which is not wiped out.

St. John Chrysostom (4th century), Homily 44 on 1st Corinthians

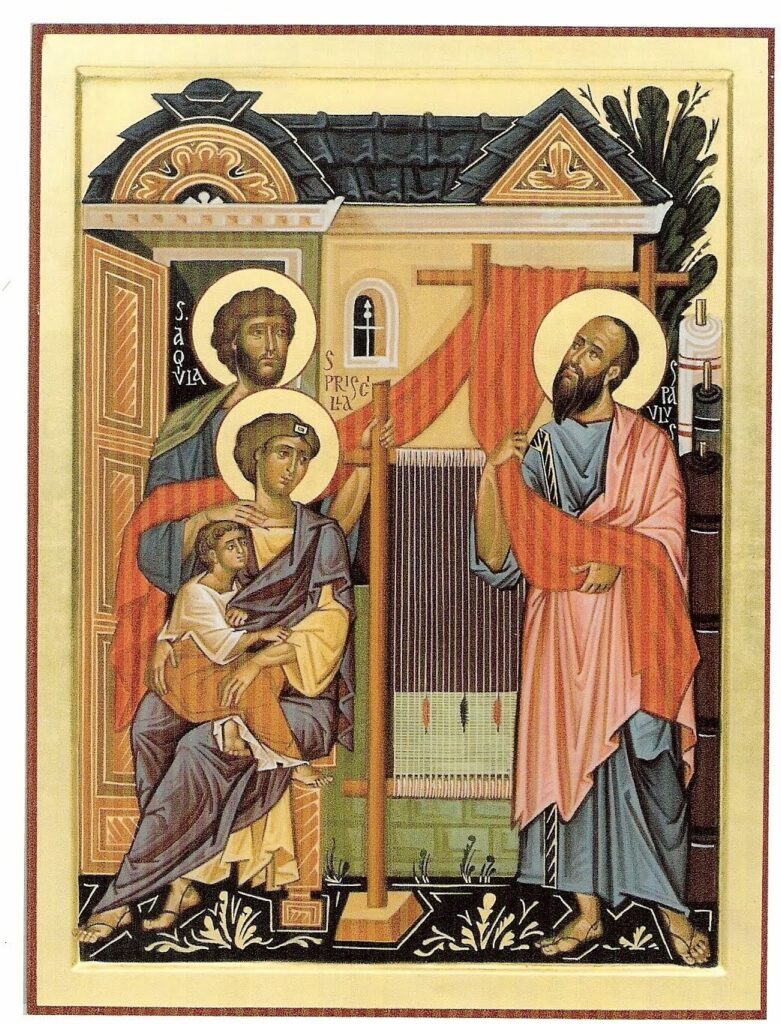

St. Paul expected his letter to be read at the Eucharist so his comments about the holy kiss and “Maranatha” are also connections to what the parish is about to do: pray together, exchange the Kiss, give thanks, and receive Holy Communion.

“Maranatha!” indeed.