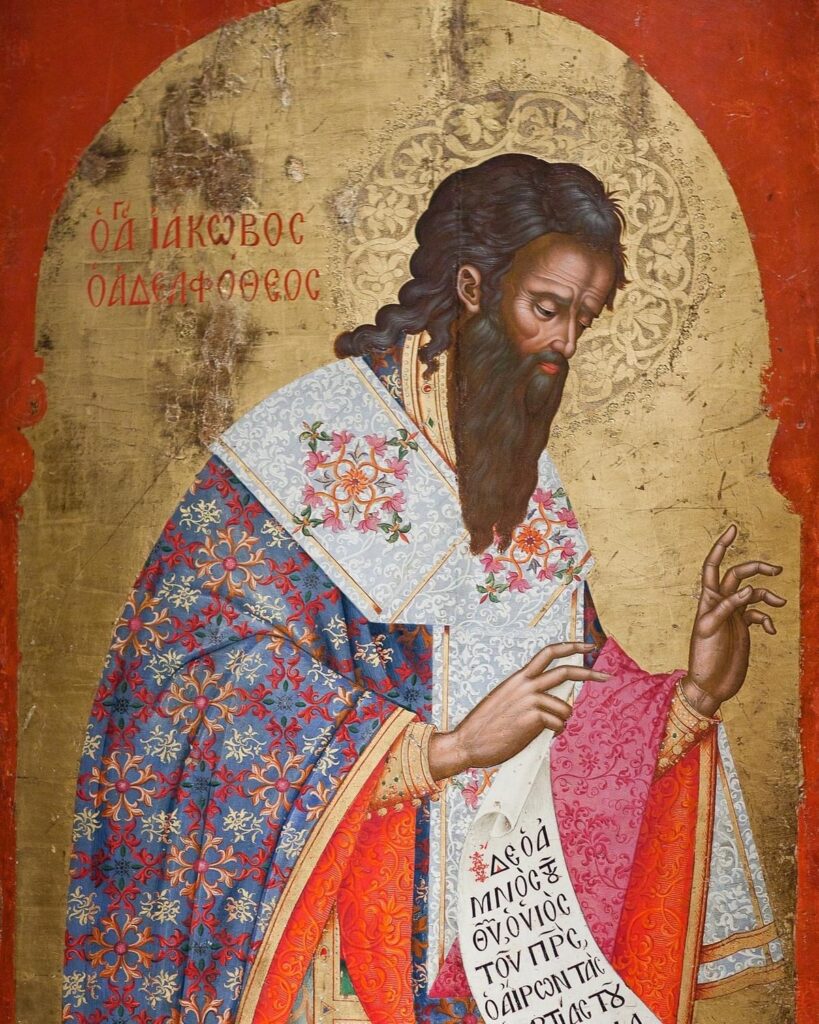

We celebrate the feast of the Apostle James on Tuesday, July 25th. He was a very popular saint in the Middle Ages and his shrine at Compostela in Spain was one of the most popular pilgrimage destinations in Europe. (The pilgrimage has become popular again in recent decades and several Episcopalians from New York have made the pilgrimage—some, several times!—in the last few years.)

St. James was an apostle, a preacher of the Good News of Jesus Christ. He spent his life traveling and sharing the message of Christ with others. He was killed because he would not deny his faith in Christ. We are likewise called to share our faith and in Christ with other people—not necessarily by traveling around the world and talking to strangers but by talking to the people we already know who live right around us already.

Our faith is important to each of us in personal and unique ways. We might feel foolish or embarrassed to discuss these reasons with people we know but we should not be embarrassed to invite people to come to church with us. If we want our parishes to grow and thrive, flourish and outlive any of us who are currently alive we need to invite people to join us on Sunday morning or at a weekday event. There are plenty to choose from.

We don’t need to wait for a special event. Every Sunday is special in some way—the music, the sermon, the fellowship at Coffee Hour. Who might you invite to join you on Sunday?

We should be praying for our neighbors as well as inviting them to come to church with us. Our prayers for the welfare of those around us can help us—and our neighbors—be more open and responsive to opportunities for sharing faith.

We believe “in one, holy, Catholic, and apostolic Church.” That means the Church is directly connected to the apostles and shares the same calling as the apostles. That means that each of us personally—because we are members of the Body of Christ, that one, holy, Catholic, and apostolic Church—also share that same calling among our neighbors and friends. We can use the feast of St. James as a reminder of our callings to be apostles just as he was.

Read previous blogs about more of the Apostle James’ adventures in Spain here.