Anyone who listens to the word but does not do what it says is like someone who looks at his face in a mirror and, after looking at himself, goes away and immediately forgets what he looks like. But whoever looks intently into the perfect law that gives freedom, and continues in it—not forgetting what they have heard, but doing it—they will be blessed in what they do. (James 1:23-25)

The “law of liberty,” the perfect law that gives freedom, sounds like a contradiction in terms, right? What law gives liberty and freedom? This law seems to be like a mirror: look into it, see yourself, and then go away and act on what you have seen-realized by gazing. Is this how normal life works?

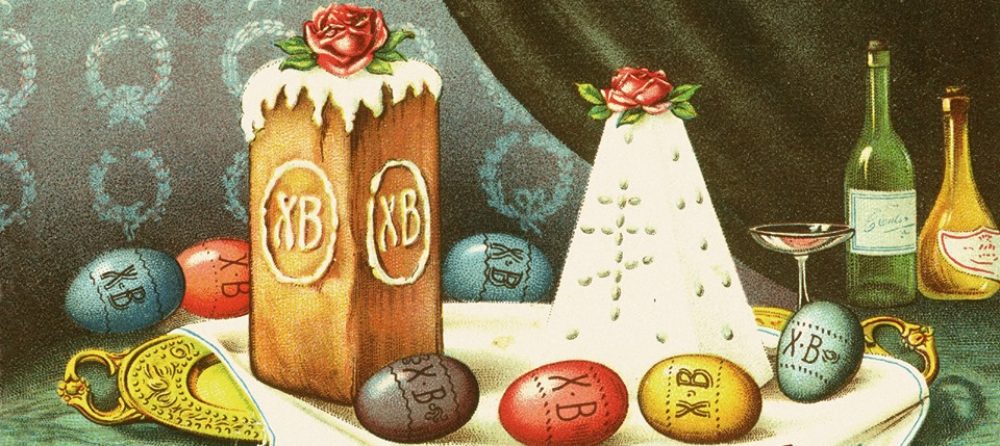

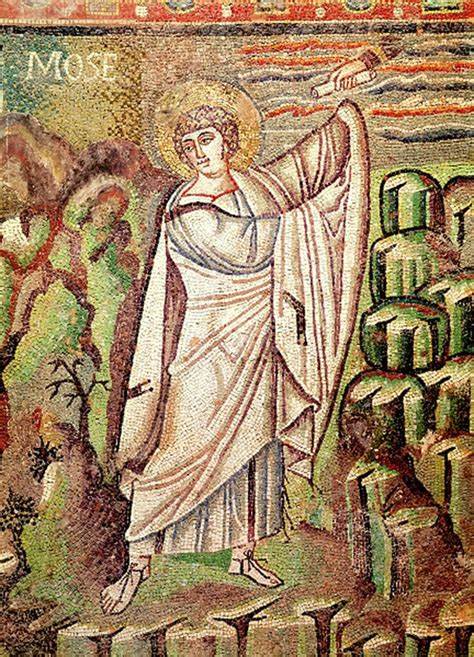

Although Moses led the people to freedom through the Red Sea, that freedom was not meant for wild parties and living high-on-the-hog, without responsibilities or duties. The freedom of Passover is fulfilled in obedience to the Law given on Mt. Sinai at Pentecost; likewise, the Resurrection of Christ is consummated by the giving of the Spirit on Pentecost–the freedom of new life is sealed by obedience. Freedom is given to the human race so that we can choose to heed the Word of God.

That’s what the “law that gives freedom” is for: by embracing it, we give ourselves to the one who liberates us from Death and are free to love; love is the summary of all the rules and all the laws ever given. Slaves cannot and do not love. Only the free can choose to love. By loving, we commit ourselves to caring. By caring, we commit ourselves to putting someone else’s needs before our own. By putting someone else’s needs before our own, we curtail our options but are able to find fulfillment in what we do, seeing the face of God in those we are committed to.