For the unbelieving husband is made holy through his wife and the unbelieving wife is made holy through her husband. (1 Cor. 7:14)

St. Paul has already discussed how a man and woman become one flesh when they have a sexual relationship, no matter how brief that relationship might be. Now he points out that because a husband and wife become one flesh, the unbelieving spouse shares in the holiness of the believing spouse.

Among the Eastern Christians, the spouse of the priest shares in her husband’s priestly ministry, to some extent. She is given a special title of respect, usually the feminine form of whatever title her husband has: presbyter/presbytera, papa(batushka)/mama (matushka), preot (priest)/preoteasa. She and the priest are one flesh and share a common relationship to the parish.

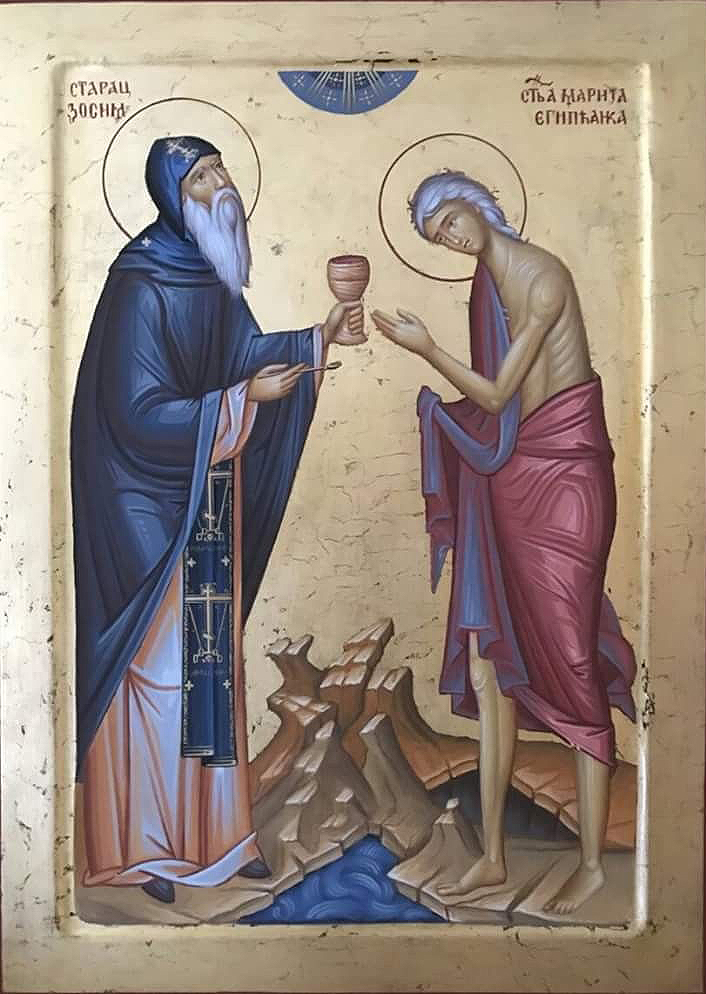

In the reception of Holy Communion, each Christian becomes one flesh with Christ and with other believers who partake. This is why the use of one loaf and one cup are so important in the celebration of the Eucharist. We all receive the same Holy Gifts and share a common life as a result.

Because we share a common life, we contribute to each other’s salvation and sanctification. The holiness of one member supports and sustains the holiness of the others; the sin of one member pulls down the others as well. “Save yourself and you will save 1,000 people around you,” said St. Seraphim of Sarov. The salvation of one radiates out to touch everyone in the vicinity–and beyond!–just a ripples from a stone thrown into a pond radiate out across the surface of the water.

“Husband and wife are one in the same way that wine and water are one when they are mixed together,” wrote the 2nd century Bible scholar Origen. The wine and water mixed in the chalice are frequently seen as an allusion to the union of divinity and humanity in Christ, as well as the union of human spouses or members of the same congregation. It is in the Paschal cup of blessing that we find our communion with God and each other.