Relics of St. Panteleimon/Panteleon in a German church (municipality Vogtsburg im Kaiserstuhl, Baden-Württemberg), Niederrotweil,

St Pantaleon Church (built 1735–1741).

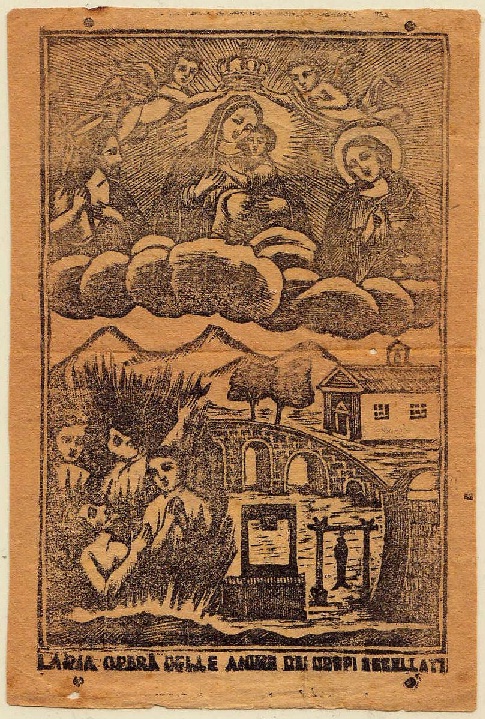

Saint Panteleimon (known by Pantaleon during his life, he changed his name shortly before his death, meaning “all-compassionate”), is counted in the West among the late-medieval Fourteen Holy Helpers and in the East as one of the Holy Unmercenary Healers. He was a physician and a martyr who was beheaded during the Great Persecution of AD 305. After the Black Death of the mid-14th century in Western Europe, as a patron saint of physicians and midwives, he came to be regarded as one of the fourteen guardian martyrs, the Fourteen Holy Helpers.

Eastern Christian icons of St. Panteleimon show him holding a small box of medicinal herbs which he can feed a patient with a spoon which he holds in his other hand. This makes him look like an Orthodox priest, about to give Holy Communion with a spoon, which underscores the connection between “health” and “salvation;” both words share a common linguistic root. Jesus’ miracles of healing in the Gospels are taken as paradigms of salvation: to be saved is to be spiritually healed and to be healed is to be saved.

When he was beheaded, his relics–including the spilled blood–were collected and preserved. A phial containing some of his blood was long preserved in the Italian city of Ravello. On the feast day of the saint (July 27), the blood is said to become fluid and to bubble.

He was also a popular saint in Venice, and he therefore gave his name to a character in the commedia dell’arte, Pantalone, a silly, wizened old man (Shakespeare’s “lean and slippered Pantaloon”) who was a caricature of Venetians. This character was portrayed as wearing trousers rather than knee breeches, and so became the origin of the name of a type of trouser called “pantaloons,” which was later shortened to “pants”.

You can read a fascinating article about St. Panteleimon and the liquid blood relic here; be sure to scroll down the page a little to find it. There is another blood relic of St. Panteleimon kept at a monastery in Madrid; you can see a television report about it here. You can also read another blog post about other saints with similar blood relics here.

A contemporary Russian icon of Saint Panteleimon, holding his spoon to administer medicine as a priest holds a spoon to share Holy Communion with the faithful.