If someone breaks into my house at night and I kill them, I’m not guilty of murder. But if the sun has begun to rise when my home is broken into, then I am guilty of murder if I kill the intruder. (Exodus 22) What’s the reason for this distinction?

Modern electricity makes us forget how dark a dark night can really be. If I kill an intruder in the middle of the night, the presumption would be that I couldn’t see who it was and couldn’t really aim —with a bat? A club? A knife or sword?—at the intruder. But if the sun has began to rise, then I can presumably see well enough to simply injure—rather than kill— the intruder.

It was dangerous in the dark. In the days before modern police or electricity, no one walked around at night unless they could afford a bodyguard. If I invited people to my house for dinner, that generally meant they would spend the night and sleep over at my house as well because it would not be safe for them to go home in the dark.

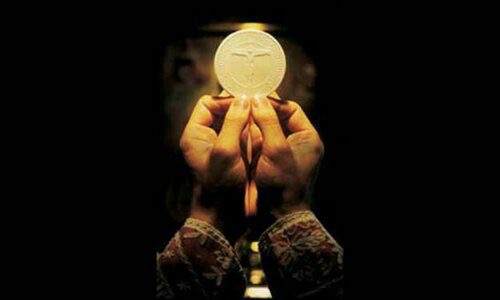

Jesus told many stories about how he would come a second time, at the End of Days, in the middle of the night. Suddenly. Unexpectedly. Without warning. Like an intruder or a thief breaking into a house. This second coming in the middle of the night was especially expected by early Christians at the Easter Vigil as the priest broke the Bread for distribution in Holy Communion. If the priest broke the Holy Bread and Christ did not return, Communion would continue as usual and the faithful would begin hoping that next year’s Easter Vigil would be the End of Days.

This expectation that Christ would return at the Breaking of the Bread came to be associated with the celebration of Holy Communion each Sunday as well. It became customary for the priest to break the Holy Bread and then pause, waiting to see if Christ would return to judge the world. If not, then Holy Communion would continue. But the whole congregation would hold their collective breath as the Bread was broken, waiting—hoping?—that today would be the day that time would end and Jesus would return.

“For when peaceful stillness encompassed everything and the night in its swift course was half spent, your all-powerful Word from heaven’s royal throne leapt down into the doomed land ….” (Wisdom 18:14-15) This description of the night of the Passover in Egypt, when the firstborn died and Moses led the Hebrews to freedom, has also been seen as a description of the first Holy Saturday (when Christ smashed the gates of Death) as well as Christmas Eve (when the Word was born in Bethlehem). It can also be the description of the End of Time as the priest breaks the Holy Bread at the Easter Vigil. Darkness can be dangerous. Darkness can also be the time of salvation.

Read about Wisdom 18 as a description of Christmas Eve here.