T

Bulls gore people. That’s what bulls do. That’s what makes Spanish bull fights exciting. It’s what makes bull herding dangerous. It’s what makes bulls dangerous to have around.

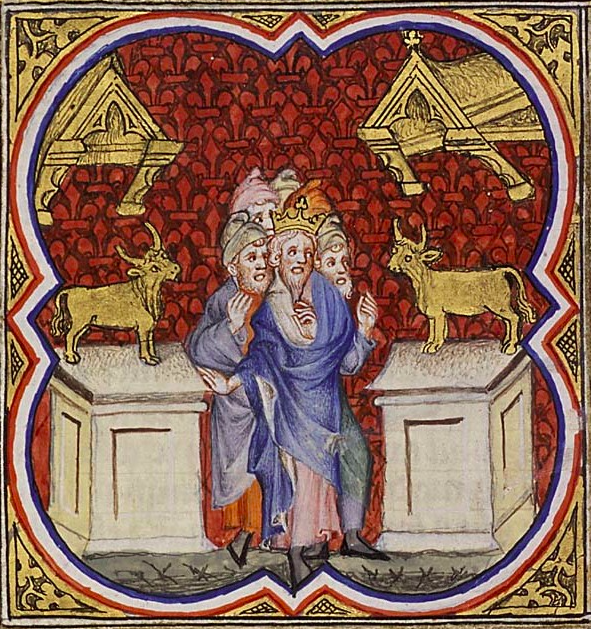

There are several commands about bulls in Exodus 21, just after Moses has been given the Ten Commandments. The text gives us three chapters of additional commandments before telling us that Moses went down from Mt. Sinai to discover that the people had begun to worship the golden calf. It’s as if the authors or editors of Exodus want us to understand that these commandments are the most important of all the commandments that were given after the Ten Commandments themselves on the two tablets of stone. Why are these commandments about bulls so important?

These commandments about bulls are important because of the possible danger to the people living in communities together. Rules for how to live together peacefully were important; rules about safety and how to settle disputes were especially important for the well-being of the People of God.

The rules about bull violence are very detailed and spell out what to do if the bull injures or kills a male or female slave, a free man, or a pregnant woman or her baby. Consequences vary, depending on if the bull has been known to injure people before or if the bull escaped its enclosure accidentally or if the owner was careless in his bull-tending.

Bulls were extremely valuable animals; anyone who owned a bull was—by definition—a rich man. Having to kill a bull that had killed someone was a severe financial loss on top of any fines the bull’s owner might be expected to pay to the community. Offering a bull voluntarily as a sacrifice was extremely expensive; such a sacrifice was especially valuable and precious.

Settling disputes involving bulls could easily become simply a matter of “might makes right” and the wealthy getting their way without any consequences for bad behavior. By having such complex rules for all the various possible situations involving violence done by bulls, Moses and Israelite society were attempting to use the law to guarantee the rights and safety of everyone, especially the poor. Throughout the Old Testament, the opposite of poverty is not wealth; throughout the Old Testament, the opposite of poverty is Justice. These rules about bulls and violence were meant to foster a just, law-abiding society. These rules were about making a society capable of welcoming the Sun of Justice when he came.

Bulls could be an image of the God of Israel (as in the psalms) or the image of a non-Israelite god. Read more about bulls in the Bible here.