Do not kill. Do no murder.

This commandment can be translated many ways. They word “kill” is often translated both ways; in other texts, when this word refers to one person, it is generally translated as “kill” but as “murder” when it refers to more than one victim.

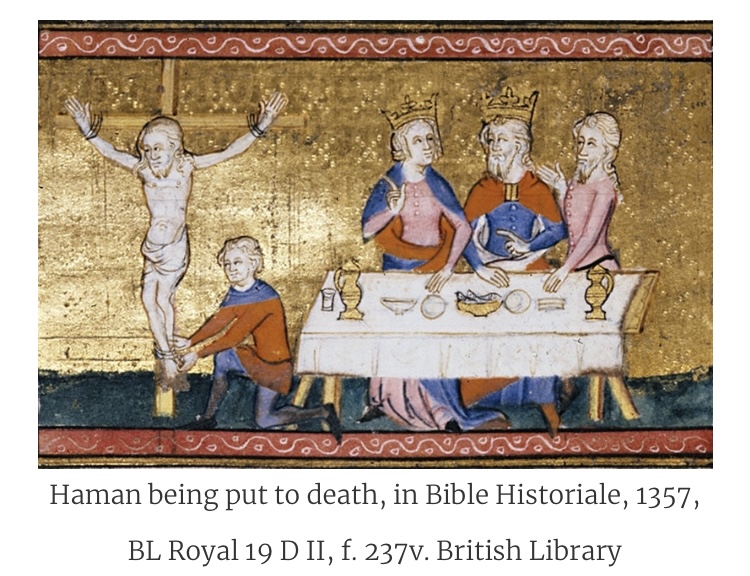

And yet there were many commandments that come with the death penalty attached. Some infractions were punished by stoning. Others were to be punished by death but no specific method of execution was stipulated. There must have been a caste of executioners in ancient Israel, similar to the priesthood, but there is no record of them. (Just as there was a caste or guild of executioners in medieval Europe, these people would know the proper methods for killing and executing people as well as the rules governing when-where-how to execute as well as the disposal of the bodies of the executed, who were generally considered ineligible for burial in standard burial grounds.)

There were also the commands that Joshua, Saul, and other ancient leaders of Israel received to commit genocide: the complete extermination of people already living in certain areas, non-Israelites occupying territory that God was giving to Israel. Slaves could be killed by their master for almost any reason—or no reason—with no consequences for the master but if killed by someone else, the killer owed a fine to the master to sample up for his lost “property.”

“Murder” is clearly not the same as “killing.” Modern law distinguishes many kinds of homocide, including manslaughter, self-defense, various degrees of murder (involving how much planning and intention the perpetrator engaged in), and accidents.

Even killing in self-defense has been treated differently by differing Christian traditions. Latin-speaking Christians said that self-defense was justified and carried no penalty; this line of thought eventually led to the “just war” theory. Greek-speaking Christians said that even justified self-defense was a traumatic experience and a person needs to undergo a modified penance to process-deal-come to terms with the experience.

Medieval Christians also gendered killing and murder differently. Killing, a strategic behavior of soldiers, was a masculine act; murder, a spontaneous or vengeful or duplicitous act, was a feminine act. Men who murdered were considered less than “real men;” women, such as a queen, who led battles or engaged in military operations, were “manly women.”

Read more about capital punishment in the Old Testament here.