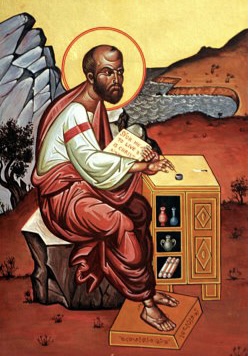

Even though our outer self is wasting away, our inner self is being renewed day by day. For the momentary light weight of our tribulation is producing a more and more exceeding and eternal weight of glory over us who are not looking to what is seen but to what is unseen; for what is seen is transitory, but what is unseen is eternal. (2 Cor. 4:16-18)

St. Paul says that although he is physically tormented and wasting away, his inner self–his spirit, his soul–is being renewed and grows stronger every day. His tribulations attack him and damage his body but he is looking forward to the glory that he will share in the Kingdom of God.

All this was true for St. Paul. What about us? We are not being attacked for our faith and tormented physically the way St. Paul was. Why do we still read this passage today? What does it have to say to us?

Not all our tribulations are caused by our mortal, political or social enemies. Sometimes our tribulations are caused by our one True Enemy, which is Death. Some people might say that the Devil is our true enemy but the Devil–the great archetype of Evil, the gigantic monster with horns and bat wings that presides over Walpurgis Night in A Night on Bald Mountain–is actually more a comic figure than a frightful, terrifying figure. In all the stories of the desert fathers and mothers, the Devil is the comic relief: he is foolish and easily duped. He is a vain narcissist and the best way to get rid of him is to laugh at him.

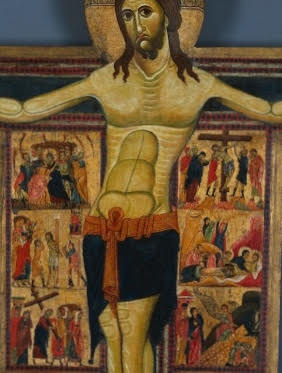

The idea that the Devil is an exaggerated figure of terror comes to us from the Puritans who reduced the invisible world to simply God and the Devil. The Puritans forgot that the one, true, ultimate enemy of the human race–and of the whole created order–is, in fact, Death itself (1 Cor. 15). Death is The Enemy that Christ mounts the Cross to wage war against. Death is The Enemy that is destroyed from the inside-out by Christ’s Death and Resurrection. If we think the Devil is the enemy, then Christ’s Resurrection becomes less the salvation of the world and more a spectacular feat without much direct meaning for us.

Sometimes we bring tribulations upon ourselves. We do something stupid and suffer the consequences. But sometimes we embrace tribulations in order to teach ourselves a lesson. That’s one of the aspects of Lent: we embrace things that are physically difficult–fasting, longer prayers or Bible reading, putting up with people who are difficult–in order to experience a little bit of Christ’s victory over Death here and now.

The renewal of the human race, begun in the sacred bath of baptism, proceeds gradually and is accomplished more quickly in some people and more slowly in others. But many are making progress toward the new life …. No one starts out perfect. To think we can be perfect without a struggle against our fallen selves is a mistake. Thinking we can be perfect without a struggle is to lead the weary astray rather than uplift the weak. Is that really what you want to do?

paraphrase of St. Augustine’s The Way of Life of the Catholic Church I.35.80

God is not a sadist. He does not want us to be miserable. But sometimes we need a little reminder that the victory was won and is being played out and extended throughout the world bit by bit. We need a physical reminder of this and so we embrace small tribulations during the tithe of the year that is Lent.