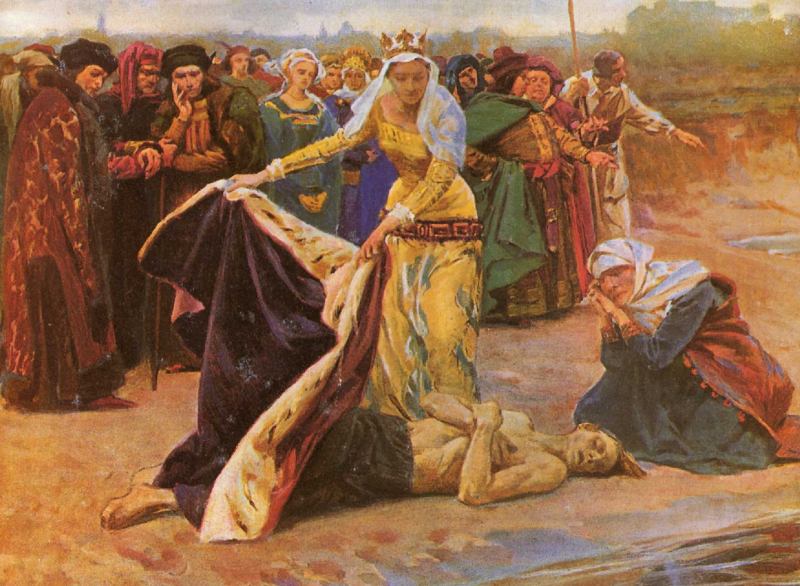

Prometheus, whose liver was gnawed by an eagle, in “Prometheus Bound” by Sir Peter Paul Rubens. The original painting is at Philly’s Museum of Art.

Nowadays, we think of our hearts as the center of our being.

“I love you with all my heart!”

“I give my heart to you!”

“I had a change of heart.”

“We need a heart-to-heart talk.”

“Don’t wear your heart on your sleeve!”

The Egyptians believed that the heart was the source of the soul and of memory, emotions, and personality. They thought that the heart would be weighed during judgement after death. So they preserved the heart during mummification but threw the brain away.

Syrians and the Arabs viewed the liver as the center of inner life. But in Hebrew tradition, kidneys were considered to be the most important internal organs along with the heart. In the Old Testament, the kidneys were associated with the most inner stirrings of emotional life. Kidneys were also viewed as the seat of the secret thoughts of the human; they are used as an omen metaphor, as a metaphor for moral discernment, for reflection and inspiration. There is also reference to the kidneys as the site of divine punishment for misdemeanors, particularly in the book of Job (whose suffering and ailments are legendary). In the first vernacular versions of the Bible in English, the translators elected to use the term “reins” instead of kidneys in differentiating the metaphoric uses of human kidneys from that of their mention as anatomic organs of sacrificial animals burned at the altar. In the Old Testament, the kidneys thus are primarily used as metaphor for the core of the person, for the area of greatest vulnerability.

The UK’s first donor kidney transplant was performed on October 30 at The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. Britain’s first kidney transplant was performed by Sir Michael Woodruff. As with the world’s first kidney transplant, the operation takes place between identical twins, reducing the chances of rejection.